I was open to it and would follow up with, "Why do you suggest that the CoolCoach Fellowship should be shorter?"

The Early Days: Open to Everything

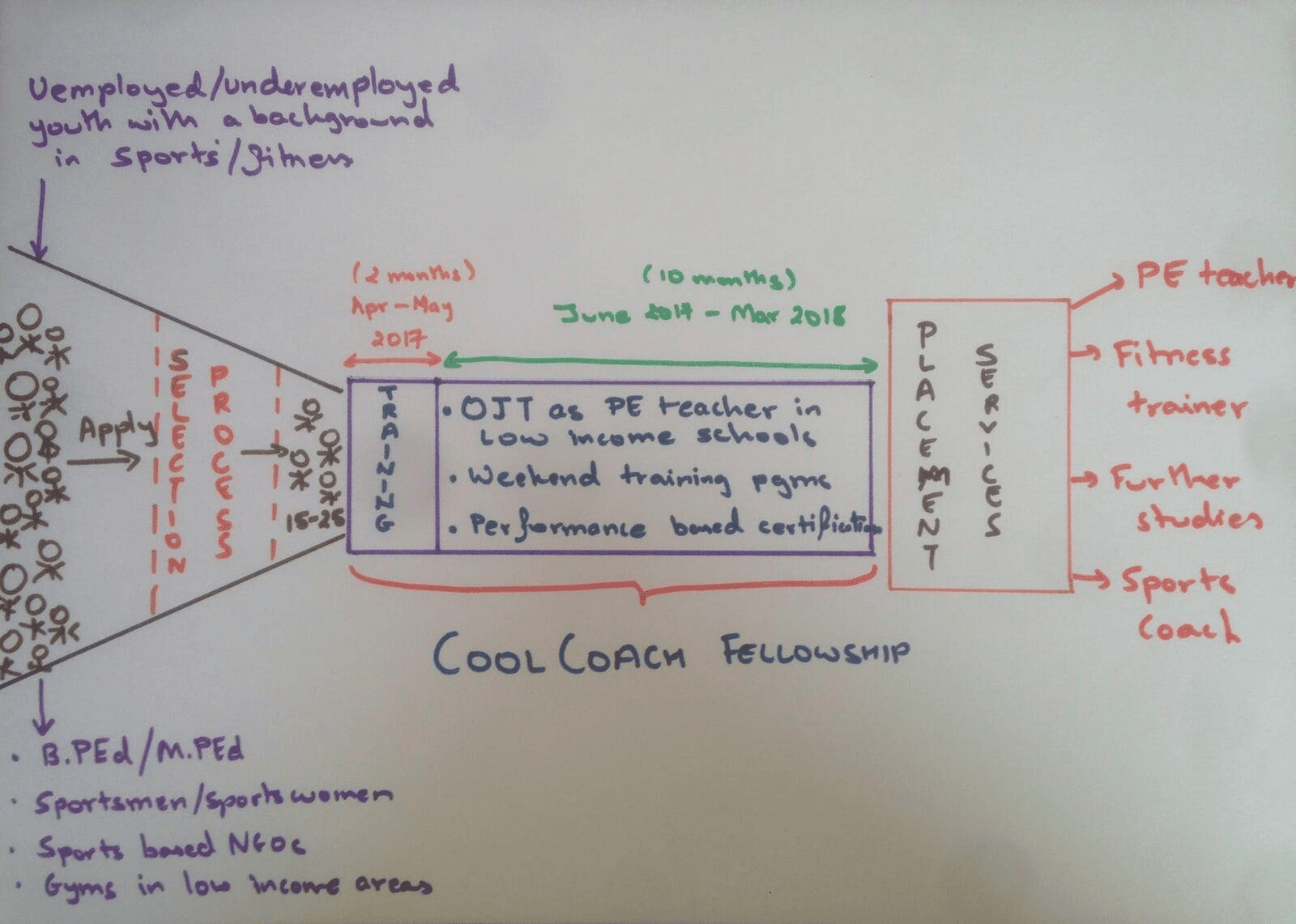

In the initial days, the Fellowship Program was still very much an idea — a figment of my imagination — and I was open to every suggestion. Based on my understanding of the Teach for America/India Fellowships (which are both two years long), my conversations with sportspersons from low-income families, and my initial research on expectations of the growing fitness industry in India, I was proposing that the CoolCoach Fellowship should be a year long. In my estimation, one year was a long enough time to upskill youth not just to get their first job in fitness, but to equip them to build a lasting career.**

The Advice I Kept Hearing

This advice usually came from people in the social sector. Invariably, I was presenting my idea because the person could support me with some combination of advice, networks, and funding. My plan included running multiple pilot programs to identify the exact length of our Fellowship program. So, when I heard their advice to reduce the length of our program, it felt encouraging. I assumed we were on the same page.

The Real Reason: Funders at the Center

But their follow up answers revealed their true reasons. In all cases, I was shocked to learn that the advice to reduce the program length did not come from prior experience of running a successful vocational training program or knowledge of one. It was to reduce the total cost of the program (to make our cost per beneficiary low) and to increase the number of batches we could hypothetically run in a year (to improve scale.)

At first glance, it sounds reasonable—lower costs, more batches, greater scale. But I realized they were designing for funders, while I was designing for the youth.

I would try and explain that we should start with a small group of youth and focus first on ensuring that we not only give them the skills to make them employable but also ensure they actually get jobs. Only after we succeed should we focus on optimization and scaling of any kind.

The App Trap: Scale Without Substance

This is where I would be further advised to use technology and apps. I would be casually told that we just need to build an app, and suddenly, sportspersons around India would be learning. Why limit the CoolCoach Fellowship Program to 15 youth, when an app could be downloaded by 150,000 youth? If scale is the goal, anything digital is so seductive. A learning app was always part of our plan, but it had a supporting role which would be fleshed out iteratively. I would try to explain that even well-funded MOOCs (Massively Open Online Courses) have single digit completion rates, why should we feel confident that an app we develop would change career outcomes for sportspersons who’ve never focused on education?

Funders would love it, they said, if we could shorten training to three months and run four batches a year. Two months and six batches? Even better. One month and twelve batches? Now we’re talking! And with an app, they added, we could reach thousands more. The numbers looked great—on a pitch deck.

I would try to remind them that the opposite of unemployment is employment, not training. Our goal is to get these youth real jobs, not just create a training program that could hypothetically reach 1000s. I was surprised when my attempts to logically discuss the advice given failed to make any impression.

Then it hit me! I had conceived the CoolCoach Fellowship Program with sportspersons from low-income families, the primary beneficiary at the centre whereas the people giving me advice were keeping the prospective funders at the centre.

The Hypocrisy: Career Paths for Whom?

I used to get upset, and I told off the first set of people after I figured out why they were giving me this advice. As subtly as possible, I would convey my frustration by reminding them about their own learning journeys to build their careers. Most of them went to good schools, invariably supported by all kinds of additional tutoring and coaching, followed by graduation from a reputed college before getting a job. Since an undergraduate degree didn't suffice for roles in senior management, they would then jump through all kinds of hoops to do a master's before feeling confident about their long-term career prospects. In short, the person giving the advice underwent 4-6 years of full-time learning after school to be career ready, but expect us — a social startup — to take youth from disadvantaged families, many of whom haven’t completed high school and have limited academic skills—and expect us to make them career-ready in just four weeks? How does that add up? And ironically, many of these same voices passionately lament the state of education each year when ASER releases its report.

What I Know Now

I still hear this advice, and I still struggle to digest it. And since we have not raised any institutional funding till date, the advice received was probably bang on if raising funds was our primary goal. I do waver. Every now and then, I wonder: who should be at the center—funders or the youth?

After running multiple pilots and successfully placing the youth we trained in the growing fitness industry in India, I am even more bullish on the time needed to upskill them. Real transformation takes time. I’d rather build something that truly works for 15 youth than fail 15,000 just to impress funders.

**Designing training to get someone their first job versus helping them build a career are two different challenges—and I’ll write about them separately.

*FRA, short for Frequently Received Advice, is a series of posts on the well-intentioned but often unhelpful advice I have received as I build CoolCoach. In most situations, I wanted to respond, and respond strongly at that, but I mostly chose to hold my tongue. Partly because I knew it was my frustration coming out, but mostly because I had no indication it would be received or understood. With these posts, I hope to share my perspective.